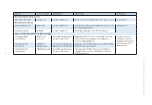

Lake Eyre Basin Rivers 224 of Queensland (2014), para. 214). There was also evidence that the ministerial briefing note and the accompanying material did not incorporate any maps showing the boundaries of the Wild Rivers areas (Koowarta v State of Queensland (2014), para. 50). There was no appeal by the state as the Wild Rivers Act 2005 was repealed by the State Development, Infrastructure and Planning (Red Tape Reduction) and Other Legislation Amendment Act 2014, soon after the Koowarta decision. The Regional Planning Interests Act 2014 now provides that the river systems in the Cape York and other regions, previously subject to Wild Rivers declarations, are rolled into the Regional Planning Interests framework as Strategic Environmental Areas (SEAs). While Cape York has a new regional plan, finalised in 2014 by the Department of Infrastructure, Local Government and Planning, the regional plans for the Channel Country (Central West and South West regions) date from 2009. For information on the protection of floodplains on Western Rivers, we refer to the Regional Planning Regulation 2014 and its guidelines (Queensland Government 2016). Under the Regional Planning Interests framework, there is protection of high value or preservation areas in the Channel Country of the Lake Eyre Basin, with a 500 m buffer either side of major tributaries and floodplain wetlands and defined riparian vegetation zones, prohibiting open cut mining, intensive agriculture and dams. There are other preservation areas outside these areas, including floodplain management areas connected to the rivers. However, environmental groups express grave concerns over the repeal of the Wild Rivers Act 2005, saying that the Regional Planning Interests Act 2014 does not provide similar high levels of protection for natural values, as it allows for other types of mining and other agricultural development (Environmental Defenders’ Office Queensland 2014). The Regional Planning Interests Act 2014 and its regulations have not built on the long and strong partnership among community, scientific and government organisations within the Lake Eyre Basin. At a transboundary level, this aspect of governance has continued to mature under the Lake Eyre Basin Agreement, which provides for collaborative management at the Basin level with the Ministerial Forum and strong input from the Scientific Advisory Panel and the Community Advisory Committee (see Chapter 7). However, this bottom-up input is not replicated at the state level, and certainly not in Queensland, which is the largest of the states constituting the Lake Eyre Basin. For the extensive river systems of the Lake Eyre Basin, a catchment which is sparsely populated, most day-to-day land management is done by graziers, Aboriginal groups, towns and some mining companies. It would be a strategic approach to formally recognise and nurture this relationship where local users and Aboriginal groups co-managed the land and resources of each of the states and the Northern Territory, consistent with the basin-level arrangements (Fig. 21.3), conferring advantages of a formal co-management relationship between state and the local community (Tan 2016). Conclusion Open, inclusive and transparent processes inspire confidence by communities in decisions of governments. While past water allocation processes, not only in Queensland, have conferred wide discretionary powers in the hands of decision-makers, present water planning frameworks seek to limit discretion in favour of sustainable management. Similarly, Wild Rivers declarations have aimed to limit deleterious development in parts of natural and near

Downloaded from CSIRO with access from at 216.73.216.152 on Nov 28, 2025, 11:59 AM. (c) CSIRO Publishing